COVID-19

What do conspiracy theories have to do with the coronavirus?

Has the coronavirus pandemic caused conspiracy theories to flourish? Actually, this cannot be verified. According to a 2020* survey by the Forum für Empirische Sozialforschung (Forum for Empirical Social Research) for the Konrad Adenauer Foundation, anti-COVID measures actually strengthened people’s belief in an intact social state. At the same time, the coronavirus pandemic has made it clear that conspiracy theories are widespread in the majority society. The thinking that creates and proliferates conspiracy theories is based in simple dichotomies and attributions of blame and corresponds with right-wing content, which it brings out in the open. Because it is assumed that the virus originated in China, anti-Asian racism has increased during the pandemic: there have been more verbal and physical attacks on people who are perceived as Asian. Not only this, but historical revisionism and antisemitism have come to play a heightened role in public debate – for example when the government and its COVID measures are equated with the Nazi dictatorship and the systematic persecution and extermination of Jewish citizens in Nazi Germany. This was noticeable, for example, when a number of people wore badges to COVID protests that resembled the Star of David and featured the word “unvaccinated” (fig. 1). In this way, they were interpreting themselves as “the new Jews.”

Fig. 1

COVID protests, Frankfurt/Main, picture alliance/dpa/Boris Roessler

Are there parallels between earlier pandemics and COVID-19?

In the effort to understand the coronavirus pandemic, a comparison is often made with the Spanish flu, which, between 1918 and 1919, claimed more lives than the First World War. Back then, people were preoccupied with how the virus spread, how to deal with it, and what its origin was – the same questions we ask today. In some countries, schools were closed, the subways stopped running, and churches closed their doors.

Documents from the time of the introduction of the smallpox vaccine likewise bring to mind the current pandemic, for example the negative stance toward vaccines, as well as the idealization or else criticism of virologists such as Christian Drosten and Sandra Ciesek. At the time, smallpox was a widespread epidemic disease that killed, blinded or disfigured its victims.

Fig. 2

Eugène-Ernest Hillemacher: “Edward Jenner Vaccinates a Boy,” oil on canvas, 1884, Wellcome Images

In 1798, Edward Jenner (1749–1823) issued a publication about the effectiveness of a smallpox vaccine, which was cowpox liquid from an infected cow that had been injected into a human subject. On May 14, 1796 Jenner vaccinated James Phipps, shown here, with cowpox from a lesion on the hand of a dairymaid named Sarah Nelmes.

Fig. 3

“The Cow Pox or the Wonderful Effects of the Inoculation,” after James Gillray, colored etching, 1802, Wellcome Images

Skepticism about the cowpox vaccine was not uncommon. In this caricature, we see Edward Jenner with a lancet, which he uses to vaccinate his patients at the London St. Pancras hospital. They have bovine features.

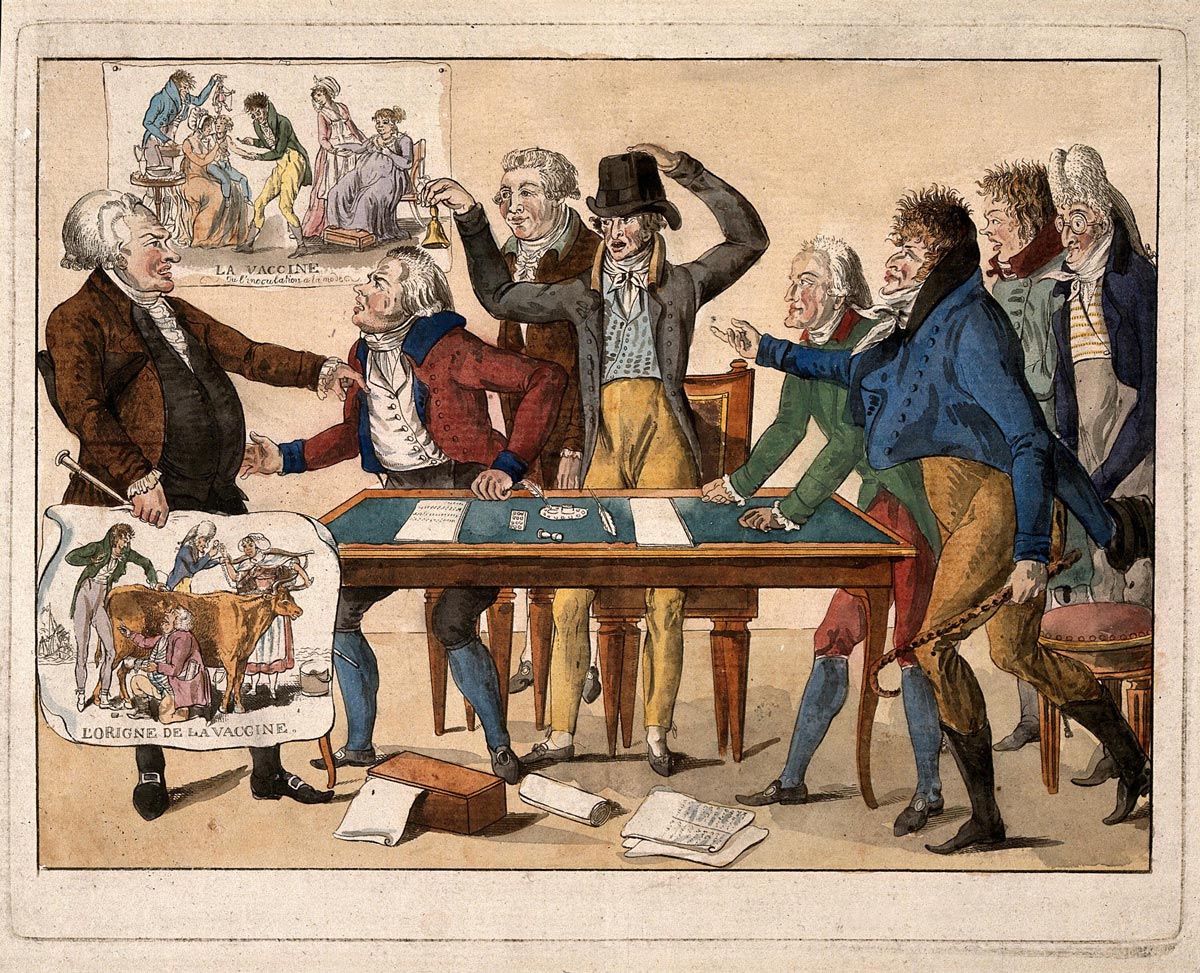

Fig. 4

“Against One, or The Vaccination Committee,” colored etching, 1801, France, Wellcome Images

In this etching, seven members of the French Vaccination Committee rail against Tapp, a health official who opposes the new discovery.

Fig. 5

“The Fall of Man in the 19th Century or The Vaccinatory Witchcraft,” after Carl Georg Gottlob Nittinger, lithograph, 1856, R. Jenni, Bern, Wellcome Images

The procession at the center of this lithograph features well-known 19th-century caricatures relating to vaccination. The team seems to be driven by Edward Jenner sitting on a cow. The words “Dr. Judas” are displayed above his head. As if on a banner, the phrase “In this spirit you will defeat God your Lord” is seen emanating from him. He pulls a wagon carrying a small-pocked woman and Death with a scythe. A man riding an ass holds a banner that reads “The non-poisonous poison.” In front of the central building of the “Jennerism Academy” there are statues of the “calf of the Jews,” the “Trojan horse” and the “bull of the Egyptians”. An owl, traditionally a symbol of knowledge but labelled “state medicine” here, flies above the peak of the building holding a quill in its beak. The buildings to the right bear writing that describes types of criminals and illnesses, for example murderers, robbers, and thieves. On the hill, a convocation of witches is in full swing; the members of the university doze in the picture’s foreground, unaware of it. At the bottom, mortality statistics for Germany and France are listed.

Images connected to Nittinger and his beliefs are often antisemitic. Those opposing vaccines traced the decline of Germany to vaccinations, which were supposedly being advanced by Jews. There were already anti-vaxxers back in the 1850s, such as Carl Georg Gottlob Nittinger (1804–1874), who came from Bietigheim, Germany. He circulated his arguments mainly through his treatise with the title “50 Years of Poisoning the People of Württemberg” with the Vaccine, which became a central reference for those who took an anti-vaccination position at the time. Nittinger criticized Edward Jenner’s publication as a “Junk Book of Case Histories,” emphasizing the harmful effects of the vaccine on population growth, military fitness, and life expectancy.

Fig. 6

“#Team Drosten,” t-shirt

Virologist Christian Drosten, who specializes in SARS virus research at Berlin’s Charité hospital, has been a central focus of public interest during the coronavirus pandemic. As a consultant to the federal government and a regular guest on the podcast “Coronavirus-Update,” Drosten became well-known among the wider public. Today, his face adorns magazines, mugs, and t-shirts.

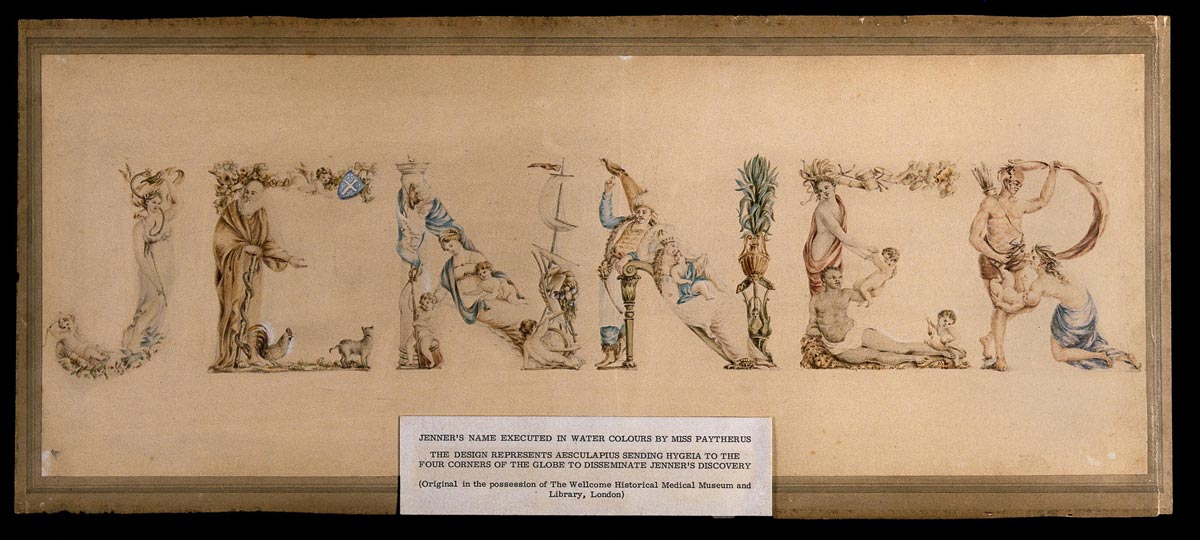

Fig. 7

Miss Paytherus: “J E N N E R,” watercolor, 19th century, Wellcome Images

Drosten’s popularity is comparable with that of Edward Jenner in the 19th century, as this watercolor shows. The letters of his name represent Asclepius, the Greco-Roman god of medicine, who is sending Hygieia, health personified, to the four corners of the globe to spread the knowledge of Jenner’s discovery.